Body Mass Index Is a Good Gauge of Body Fat

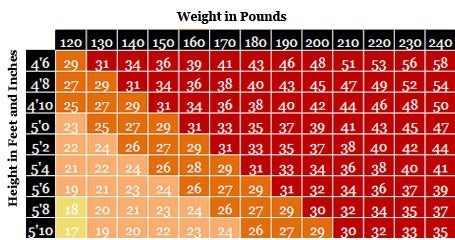

The most basic definition of overweight and obesity is having too much body fat-so much so that it “presents a risk to health.” (1) A reliable way to determine whether a person has too much body fat is to calculate the ratio of their weight to their height squared. This ratio, called the body mass index (BMI), accounts for the fact that taller people have more tissue than shorter people, and so they tend to weigh more.

- You can calculate BMI on your own, or use an online calculator such as this one, by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

BMI is not a perfect measure, because it does not directly assess body fat. Muscle and bone are denser than fat, so an athlete or muscular person may have a high BMI, yet not have too much fat. But most people are not athletes, and for most people, BMI is a very good gauge of their level of body fat.

- Research has shown that BMI is strongly correlated with the gold-standard methods for measuring body fat. (2) And it is an easy way for clinicians to screen who might be at greater risk of health problems due to their weight. (3,4)

Healthy BMI in Adults

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that for adults, the healthy range for BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9.

- Overweight is defined as a body mass index of 25 to 29.9, and obesity is defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher. (1) These BMI cut points in adults are the same for men and women, regardless of their age.

- Worldwide, an estimated 1.5 billion adults over the age of 20-about 34 percent of the world’s adult population-are overweight or obese. (5) By 2030, this is expected to rise to more than 3 billion people. (6)

For clinical and research purposes, obesity is divided into three categories: Class I (30-34.9), Class II (35-39.9) and Class III (?40). (7) With the growth of extreme obesity, researchers and clinicians have further divided Class III into super-obesity (BMI 50-59) and super-super obesity (BMI?60).

Risk of developing health problems, including several chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, rises progressively for BMIs above 21. (7) So does the risk of dying early. (8, 9) There’s also evidence that at a given BMI, the risk of disease is higher in some ethnic groups than others.

Weight Gain in Adulthood Increases Disease Risk

In adults, weight gain usually means adding more body fat, not more muscle. Weight gain in adulthood increases disease risk even for people whose BMI remains in the normal range.

- In the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, for example, middle-aged women and men who gained 11 to 22 pounds after age 20 were up to three times more likely to develop heart disease, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and gallstones than those who gained five pounds or fewer.

- Those who gained more than 22 pounds had an even larger risk of developing these diseases. (10–14)

- A more recent analysis of Nurses’ Health Study data found that adult weight gain-even after menopause-can increase the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. (15)

Healthy BMI in Children and Adolescents

It is normal for children to have different amounts of body fat at different ages, and for girls and boys to have different amounts of body fat. (16) So in children and teens, the healthy range for BMI varies based on age and gender.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed standard growth charts for boys and girls ages 2-20 that show the distribution of BMI values at each age. By the CDC’s definition, a child whose BMI falls between the 85th and 94th percentile for age and gender is considered overweight. A child whose BMI is at the 95th percentile or higher for age is considered obese.

In 2006, the WHO developed international growth standards for children from birth to age 5, using healthy breast fed infants as the norm; (17) in 2007, the WHO extended those standards to develop growth charts for children ages 5 to 19. (18) Breastfed infants tend to gain weight more slowly than formula fed infants after 3 months of age, so the WHO growth standards have lower cut points for underweight and overweight to reflect this difference. The CDC now recommends using modified versions of the WHO growth standards for all children from birth to age 2. (19) The International Obesity Task Force has also developed its own cut points for childhood overweight and obesity. (20) At different ages, these criteria give somewhat different estimates of overweight and obesity prevalence. (Read more about the dueling definitions of childhood overweight and obesity.)

BMI vs. Waist Circumference: Which Is Better at Predicting Disease Risk?

Body fat location is also important-and could be a better indicator of disease risk than the amount body fat.

- Fat that accumulates around the waist and chest (what’s called abdominal adiposity) may be more dangerous for long-term health than fat that accumulates around the hips and thighs. (21)

Some researchers have argued that BMI should be discarded in favor of measures such as waist circumference. (22) However, this is unlikely to happen given that BMI is easier to measure, has a long history of use-and most important, does an excellent job of predicting disease risk.

In adults, measuring both BMI and waist circumference may actually be a better way to predict someone’s weight-related risk. (23) In children, however, we don’t yet have good reference data for waist circumference, so BMI-for-age is probably the best measure to use.

- As obesity rates have soared, people’s perceptions of what constitutes a healthy weight appear to have shifted: A recent U.S. study comparing weight perception surveys from the late 1980s to the early 2000s found that in the early 2000s, people were more likely to consider their own weight “about right” instead of “overweight.” (24) Some of these people were truly at a healthy weight, but many of them were not.

- Measuring BMI (and in children, BMI percentile-for-age) and tracking it over time offers a simple and reliable way for people to tell whether they are indeed at a healthy weight.

References

1. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet Number 311. September 2006. Accessed January 25, 2012.

2. Gallagher D, Visser M, Sepulveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? Am J Epidemiol. 1996; 143:228-39.

3. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003; 139:930-2.

4. Barton M. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2010; 125:361-7.

5. Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet. 2011; 377:557-67.

6. Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int.J.Obes. (Lond). 2008; 32:1431-7.

7. James WPT, Jackson-Leach R, Ni Mhurchu C, et al. Chapter 8: Overweight and obesity (high body mass index). In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, eds. Comparative quantification of health risks: Global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004.

8. Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:763-78.

9. Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, et al. Body weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:677-85.

10. Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, et al. Body size and fat distribution as predictors of coronary heart disease among middle-aged and older US men. Am J Epidemiol. 1995; 141:1117-27.

11. Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Weight, weight change, and coronary heart disease in women. Risk within the ‘normal’ weight range. JAMA. 1995; 273:461-5.

12. Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 122:481-6.

13. Maclure KM, Hayes KC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. Weight, diet, and the risk of symptomatic gallstones in middle-aged women. N Engl J Med. 1989; 321:563-9.

14. Huang Z, Willett WC, Manson JE, et al. Body weight, weight change, and risk for hypertension in women. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 128:81-8.

15. Eliassen AH, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA. 2006; 296:193-201.

16. Kuczmarski R, Ogden, CL, Guo, SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. National Center for Health Statistics. 2002. Accessed January 25, 2012.

17. World Health Organization. The WHO Child Growth Standards. Accessed January 25, 2012.

18. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007; 85:660-7.

19. Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF. Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0-59 months in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59:1-15.

20. Monasta L, Lobstein T, Cole TJ, Vignerov J, Cattaneo A. Defining overweight and obesity in pre-school children: IOTF reference or WHO standard? Obes Rev. 2011;12:295-300.

21. Hu FB. Obesity and mortality: watch your waist, not just your weight. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167:875-6.

22. Kragelund C, Omland T. A farewell to body-mass index? Lancet. 2005; 366:1589-91.

23. Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008; 117:1658-67.

24. Burke MA, Heiland FW, Nadler CM. From “overweight” to “about right”: evidence of a generational shift in body weight norms. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010; 18:1226-34.