Mass & Cass, the community that surrounds the intersection of Massachusetts Ave. and Melnea Cass Blvd. on the border of the South End and Roxbury, has been at the forefront of the headlines about substance use in Boston. While Mass & Cass is a visible example of the substance use crisis in Boston, the reality is that people who use drugs have many less visible needs. Of the over 600 overdose deaths in Boston between 2019 and 2021, 93% happened outside of the Mass & Cass zip code and, more often, in people’s homes.

Mass & Cass, the community that surrounds the intersection of Massachusetts Ave. and Melnea Cass Blvd. on the border of the South End and Roxbury, has been at the forefront of the headlines about substance use in Boston. While Mass & Cass is a visible example of the substance use crisis in Boston, the reality is that people who use drugs have many less visible needs. Of the over 600 overdose deaths in Boston between 2019 and 2021, 93% happened outside of the Mass & Cass zip code and, more often, in people’s homes.

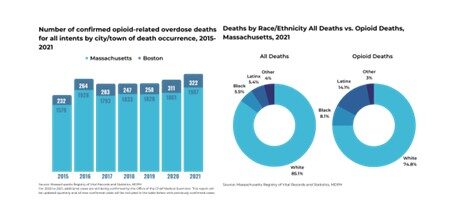

The needs of people who use drugs in Boston and Massachusetts are ever-changing and increasingly urgent to address. Overdose deaths have reached an all-time high in Boston and Massachusetts. In 2021, Massachusetts reached the highest number of overdose deaths ever with 2,290 overdose fatalities, 322 of which were in Boston. Black & Latinx deaths were only about 10% of all deaths statewide but 22% of fatal overdoses. The highest overdose death rate in Massachusetts is among American Indians followed by Black and Latinx men.

At the same time, Boston experienced an outbreak of HIV infections among people who use drugs, a population whose HIV rates had been stable nationally for years. However, between early 2019 and March 2021, 113 new HIV cases in Boston were associated with a cluster among people who inject drugs.

The risk of overdose and infectious disease concerns continue to increase as the drug supply changes, as well. Fentanyl, a highly potent synthetic opioid, was present in 93% of deaths where a toxicology report was available. The  drug supply is now not only laced with fentanyl, but a new method of cutting drugs has introduced xylazine, an animal tranquilizer, into the supply, which increases the risk of overdose because it is associated with unconsciousness, slowed heart rate and decreased breathing.

drug supply is now not only laced with fentanyl, but a new method of cutting drugs has introduced xylazine, an animal tranquilizer, into the supply, which increases the risk of overdose because it is associated with unconsciousness, slowed heart rate and decreased breathing.

The status quo is not working for people who use drugs, in the streets or in their homes. The public safety and public health impact of drug use call for a paradigm shift in meeting the needs of people who use drugs. In 2019, the Massachusetts Harm Reduction Commission recommended that “a pilot program of one or more [overdose prevention centers] should be part of the Commonwealth’s efforts to combat the opioid crisis.” It is time we heed this call and give Overdose Prevention Centers a try.

OPCs are facilities where people can use their own drugs under the safety and supervision of trained staff without being prosecuted for drug possession. The goals of OPCs are twofold: 1) to ensure that people who are using drugs are safe, whether that means that staff are available to respond to an overdose, equipment is available to prevent infections or infectious diseases, or drug testing is available to inform the individual of the drugs they are consuming; and 2) to reduce the negative health and safety outcomes that are associated with public drug consumption, particularly public injection, by ensuring people are not injecting or using in the streets (or alone) and safely disposing of used equipment.

Studies of OPCs have demonstrated a reduction in overdose deaths, overdose mortality, and all-cause mortality; an increase in referrals including uptake of detoxification services, reduction in risk behaviors that spread disease, like syringe sharing or re-using; a reduction in HIV transmissions; and fewer ambulance calls for overdoses. At the same time, OPCs have led to decreases in crime or have had no impact on crime rates in the surrounding areas, with reductions in outdoor public injection and fewer publicly discarded syringes, while promoting a sense of social acceptance among participants, and reducing costs. The evidence is clear – OPCs work.

Addressing the opioid epidemic in Boston requires a comprehensive approach that addresses public safety, preventing overdose deaths in the streets and in homes, and addressing outdoor consumption in addition to the housing priorities Mayor Michelle Wu has already outlined. OPCs expand our toolbox to address many of these issues.

Boston has an opportunity to learn from other cities pushing the envelope already. Somerville has already started this conversation locally and released several feasibility and assessment reports, and Rhode Island’s legislature has sanctioned OPCs in their state. In November 2021, NYC became the first city in the nation to legally sanction OPCs when OnPoint NYC opened their sites in East Harlem and Washington Heights, with great success.

We need drug use policies that acknowledge the complexity of drug use and provide people who use drugs with dignity, respect, and humane treatment that will help save their lives. That is what OPCs do. They are not just places for people to come and use and leave – they are life-affirming, life-saving spaces that provide people a chance to live another day.