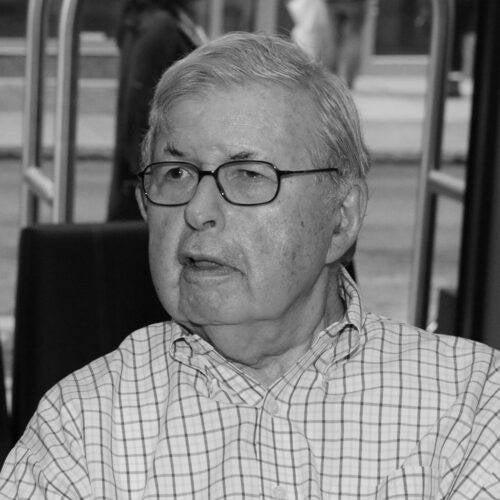

Henry Wechsler, who was an important and valued member of SBS and faculty of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health for 40 years, passed away in November 2021. A social psychologist, his research interests included alcohol and drug abuse among young adults and ways to reduce their high-risk behaviors. He retired from Harvard Chan in 2006.

Wechsler was the principal investigator of the College Alcohol Study, funded by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, that focused on the key issues of college alcohol abuses, notably binge drinking From 1993 to 2001, The study conducted four national surveys involving over 50,000 students across 40 states.

We have gathered here our fond recollections of our colleague, mentor, and teacher.

Steven Gortmaker, Professor of Social & Behavioral Sciences

Henry was such a valued member of our department, and his work with the College Alcohol Study transformed the way we measure and think about alcohol use and abuse, and “binge-drinking.” Henry and his team conducted seminal work in this area and helped develop and evaluate effective alcohol abuse prevention strategies.

I always valued Henry’s wise counsel and wonderful friendship.

Subu Subramanian, Professor of Population Health and Geography

I had the privilege and fortune of serving on a dissertation committee of Henry’s student – Toben. I was a young faculty just starting out. And recall vividly my interactions with him on applying a multilevel perspective to his novel project, College Alcohol Study. He was one of the kindest persons and always was a force from behind pushing young talent. He was always available to share his advice and counsel with students and junior faculty such as myself.

Toben Nelson, ScD (2005), Professor in the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health

Henry lived a long, productive, and impactful life. He retired on his own terms at the top of his career. When I worked with him he mostly preferred to be at his home office. He came into HSPH a few times a month but rarely traveled. At every conference I attended while I was at Harvard and since I have been at Minnesota, our colleagues asked about Henry and asked me to say hello. People in our field held him in high regard and recognized his significant contributions.

It is hard to sum up the impact that Henry Wechsler had on my life. He was a mentor and a friend. I regularly reflect on how fortunate I was to get to work with him. I think I was aware of our special relationship at the time we were working most closely together, but it has become even more clear in retrospect. He was a true scholar. He was generous and kind. He gave me countless opportunities to contribute to his projects. Henry was always most engaged talking about research, whether it was talking about survey item development, paper ideas, analysis, or editing a manuscript. He loved what he did and his enthusiasm for the work and the academic life was infectious. Every day I apply ideas and approaches I learned from Henry. And I can often recall the exact conversation when he shared his insights with me.

I knew I would never be able to reciprocate everything he has done for me. I do try to pay it forward with my own students. Thank you for the opportunity to remember and share my experiences with Henry.

Eric Rimm, Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition, HSPH

I worked with Henry for several years when I was a post-doc on a project related to binge drinking. He reached out to me because he needed someone who could handle this unique data set. What a lovely opportunity for me as a trainee studying moderate alcohol and chronic disease, to work with a study of the reverse and strongly adverse consequences of excess alcohol consumption. Little did Henry know, but our paper that quantitated levels of intake at which adverse effects life events occurred (e.g. getting into fights, injury from falling down, blacking out) became the foundation for how the US and countries across the world define “binge drinking” in population studies and in national guidelines. I recall sitting with Henry and our colleague George Dowdall, who was a sociologist working on public health among college students, and talking through the implications of defining a different sex-specific cut-off for binge drinking. It was clearly evidenced based and the levels at which young college men and women got into trouble when they over-consumed. Henry was quite sharing with his ideas and time, but also very clear with his writing and with his interpretation of the data. His work has changed and pushed college presidents across the country and world to be vigilant about addressing alcohol abuse in college campuses. May his many papers on the dangers of excess alcohol consumption in college students be a reminder of how one person can make important contributions to humanity. Rest in peace in my friend.

George Dowdall, Adjunct Fellow, University of Pennsylvania Center for Public Health Initiatives & Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University

Henry Wechsler’s passing has saddened all of us who had the opportunity to know him and to collaborate with him. He leaves behind a body of work that has transformed the study not only of college alcohol use but of alcohol use in the general population, and of campus safety and security.

I joined Henry’s group at the Harvard School of Public Health in 1994 and served as a visiting lecturer just as Henry was launching the first HSPH College Alcohol Study. I will confine my comments to the parts of the CAS I was directly involved in, hoping that others will fill in other parts of his long career. CAS was generously funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which also included support for public dissemination of the results. A detailed questionnaire was completed by over 17,000 full-time undergraduates at 140 four-year institutions of higher education. Representative samples of both colleges and students, a high response rate, a comprehensive list of precursors and consequences of drinking, and a focus on the environment made the CAS the preeminent study of college drinking in its day. Henry once remarked that his “bible” was Drinking in College, the classic 1953 study by Straus and Bacon and a landmark in alcohol studies. His own work both updated and greatly extended that work.

The key concept of the CAS was “binge drinking,” a term that Henry redefined from its prior use as a several-day drinking spree to a measure of heavy episodic drinking. He had earlier used the term in his study of Massachusetts colleges. He and his Harvard collaborators introduced the “5/4” definition of binge drinking: five or more drinks in a row for males and four or more drinks in a row for females in the two weeks before the questionnaire was completed. The concept neatly contained both the quantity and frequency of alcohol use. Henry’s paper in the American Journal of Public Health (1995), coauthored by Andrea Davenport, Eric Rimm, and me, explained the need for and construction of a gender-specific measure. While the concept proved controversial, later empirical research would confirm its utility in studying both adolescent and adult alcohol use. It became a standard phrase in popular culture and a widely-used measure in both American and international alcohol studies and public health.

A 1994 in the Journal of the American Medical Association used CAS data to explore the health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. Henry was senior author of this paper, co-authored by Andrea Davenport, Barbara Moeykens, Sonia Castillo, and me, with technical assistance from Jeff Hansen. All of us were then staff members of the CAS, with administrative leadership from Diana Chapman Walsh, chair of the Department of Health and Social Behavior, project administration from Marianne Lee, and collegial support from other members of the department.

Far from being a harmless rite of passage, binge drinking often had serious consequences for both the drinker and those nearby, which Henry termed “secondhand binge effects.” Clear gradients of Individual harm were observed, from the least among nondrinking or nonbinging students to the greatest among frequent binge drinkers (who binged 3-5 times in the two-week period). About two in five students overall were binge drinkers, but at roughly a third of the colleges, more than 50 percent of students were binge drinkers. At the college level, these “high binge campuses” had the highest rates of alcohol-related problems.

Henry was not only a very productive individual researcher, but proved remarkably capable of inviting collaboration with many others at both Harvard and at other institutions; the list is far too large to print here. Three more CAS surveys were done in 1997, 1999, and 2001, and then Henry collaborated on several waves of studies at high-binge campuses. The results included over 80 peer-reviewed papers and several books and monographs that explored how the college context and environment shaped binge drinking and its consequences.

Henry was also a superb example of how a researcher can simultaneously contribute to a scientific literature while fostering a broad conversation about a public health problem. His CAS studies were often announced in a press conference format, sometimes with the participation of a leading public figure. One personal anecdote comes to mind. Thanks to Henry’s support, I served in 2000 as a Congressional Fellow in the office of then-Senator Joe Biden. Senator Biden had introduced a sense of the Senate resolution about binge drinking and produced a Senate report on excessive college drinking. I had arranged for him to appear at HSPH at the release of a new CAS study. But just days away from the press conference, Senator Biden found me in a Senate hallway and said, “George, I’m sorry that I can’t join you at Henry’s meeting in Boston, but as the ranking Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee, I’ve got to go that day to meet with the new Russian leader in Paris. Have you heard of Vladimir Putin?”

Henry’s contributions were broader than just to alcohol studies. I recently had the opportunity to review the large literature on alcohol-related campus crime; most campus crime has an alcohol component. A 2016 National Institute of Justice paper summarized the research on campus sexual assault published in 34 papers from 2000 to 2015. Among them was a 2004 paper produced by Henry and several collaborators (Meichun Mohler-Kuo, Mary Koss, and me) from the CAS data. The paper was (and remains to this day) the only one using a large probability sample of both students and institutions across several different points in time. Roughly one in 20 college women experienced rape during the past academic year, and of that number more than 70 percent were too intoxicated to provide consent for sex. More recently, a paper by a prominent researcher found that all women who had experienced intoxicated rape in her sample were binge drinkers. While the rapist is always responsible for sexual assault, the CAS findings had made clear that alcohol use raises the risk of victimization and points toward promising paths for prevention.

On a more personal level, I am only one of the many people with whom Henry collaborated and worked. He was a very generative person, and I’m certainly not alone in being one of the people whose careers were greatly strengthened by working with him. Henry was a wonderful colleague and his single-minded focus was simply remarkable. Working with him on a daily basis was a real pleasure, inevitably including reports of his erratic tennis career and the even more erratic performance of a Saab that required imported parts seemingly handcrafted by Swedish royalty. For a man devoted to studying a very serious public health problem, he had a wonderful sense of humor and supplied endless puns. Finally, and most importantly, Henry was deeply devoted to his wife Joan and very proud of his children and their achievements.

He will be deeply missed.

[From 1994 to 1997 George Dowdall was a visiting lecturer at the Department of Health and Social Behavior of the Harvard School of Public Health. He served as a staff member of and then consultant to the HSPH College Alcohol Study.]

Charles Deutsch, ScD, formerly Senior Research Scientist in the Department.

Henry was a wonderful mentor, though I wasn’t always a dutiful mentee. I didn’t see myself as an academic researcher, and had written curricula for the CDC and published a book on helping children of alcoholics before I entered the doctoral program at HSPH. (One professor told me I’d have to learn how to write “journalese” and, as a language lover, I was pretty sure I didn’t want to do that.)

I think I first met Henry when he asked me to teach a section of his course on alcohol use, and I continued to do that for several years. Along with his research on drinking among college students, in his role at The Medical Foundation he had WT Grant Foundation support for a study of the sources, responses, and symptoms of stress among students. He surveyed students at sixteen Massachusetts colleges in 1981. By securing permission from freshmen for a follow-up study, and having them complete self-generated identifying codes, he and his team laid the groundwork for the panel study on stability and change in drinking patterns that became my dissertation.

Like many people, I had a lot going on while I was doing my doctorate – I had speaking invitations due to my book, my second and third children born, a part-time job and consulting gigs. Fortunately, Henry had an abundance of patience to go with his relentless encouragement. But he was also impatient, in the best way, for impact: For example he, George Dowdall and I published an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education that reached a broader audience than health-related academic journals.

As everyone who knew him knows, Henry had an indefatigable sense of humor, delivered with a twinkle in the eye and the smallest puckish grin on his lips. As others have said, he was effective, admired, and loved, both for what he did and what he was.

Laura Kubzansky, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Social & Behavioral Sciences

Henry was wonderfully supportive when I came to Harvard – Sol Levine introduced me to him and shortly thereafter Henry invited me to work with him and his team. He was unfailingly generous with his time and his ideas. This generosity is what I remember best. And his belief that with this work, we could make the world a better place.

Rima Rudd, Senior Lecturer, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences

Henry took delight in the fact that his greatest project was his last – Ending on a high note!

He had shared stories of his arduous journey here to the U.S. Ellis Island did not quite offer open arms of welcome but, over time, the country offered so much.

At faculty meetings, he came to the table in good spirits, ready to engage.

I’m happy to have had opportunities to explore ideas with him.

Marla Eisenberg, ScD (2001), Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School

I worked with Henry from 1999-2001, when I was a doctoral student in what was then called the Department of Health and Social Behavior. I had heard of the College Alcohol Study, of course, and knew that Henry had a wealth of experience in survey research and deep expertise in substance use behaviors among college students. He had added new survey questions to the CAS survey about sexual behavior – including one about having same-sex partners, which was almost unheard of in population-based research at the time. Henry was extremely generous in letting me run with these new items for my dissertation. It was a very new field, and we published four papers using those data, which launched my career in LGBTQ adolescent and young adult health. I am very grateful to have benefited from his leadership and mentorship.

Picture: From left: Lisa Berkman (Chair of Department at the time), Marla Eisenberg, Henry Wechsler, Glorian Sorensen.

Glorian Sorensen, Professor, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences

I remember Henry’s sparkle so clearly. Funny how little memories stick – that each week he did the Sunday NYT crossword puzzle in ink.

Vaughan Rees, Senior Lecturer, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences

When I joined the SBS faculty in 2012 Dr. Wechsler had been retired for several years, but his influence loomed particularly large for me. His body of work on substance use—alcohol use in particular—had achieved almost universal recognition in public health circles. My SBS colleagues often referenced Henry’s work, and colleagues from institutions across the country assumed that others at Harvard were working on new iterations of Henry’s groundbreaking research. Henry’s seminal College Alcohol Study exerted influence on alcohol policy in the U.S. long after the last paper was published, and continues to echo strongly across government, college and high school administrations. I had the fortunate opportunity to take over SBS 219: a course originally developed by Henry on prevention of high-risk behaviors. This course is still being taught each year to a new class of budding public health professionals eager to gain deeper understanding on approaches to protecting the health of vulnerable young people. Henry Wechsler, the esteemed SBS faculty member I never met, through his gifts of scientific skill and far-sightedness, has wielded profound impact on the lives of many in the Harvard community and beyond.

Ichiro Kawachi, John L Loeb & Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Social Epidemiology

Henry retired from the Department in 2008. Just before his retirement, he and his wife Joan graciously offered to host a departmental party at their home in Quincy. I remember fragments from our conversation over drinks (for the record, I had a glass of wine, Henry had juice). I asked him if he was worried about retiring in the middle of a looming financial crisis. “Not at all,” he chuckled, he had invested very prudently, and was looking forward to kicking back after 40 years of teaching at Harvard. He was very content to follow the exploits of his daughter Pamela who was a prosecutor and assistant district attorney in Boston.

However, the mind of an academic never truly “retires”. In 2013, Henry wrote to me: “I have been academically inactive for more than 5 years now. While the brain of an octogenarian may be a bit slower, it still shows signs of life.” He had a new proposal to revive his College Alcohol Study to examine the impact of the changes in marijuana legislation in different U.S. states on changes in marijuana use by college students. It was a beautiful natural experiment. Ultimately, his proposal was declined by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation because of their changed priorities, but I still think about what a blast it would have been to lure him out of retirement to run his study again. I miss his collegiality, his gentle voice, his wise counsel.

Elissa Weitzman, MSc (1989), ScD (1999), Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School

To know Professor Henry Wechsler was to appreciate the value of wry humor, a well-timed quip, academic curiosity, and love of family. I recall sitting in a room with him when a major media outlet called for a comment about another social scientist’s assertions, “Well, you can always tell a Yale man, you just can’t tell him much.” Listening to a colleague lament about too little office space, Henry noted, “If you got rid of all the difficult personalities at Harvard, you would solve the space problem…”. He was funny. Because he was low key by nature, you didn’t expect the wit – adding to the laugh. I worked with Henry throughout my doctoral training at the Harvard School of Public Health. Academically, he put college drinking on the map – coined the term ‘binge drinking’, quantified primary and secondhand effects of these behaviors for youth and the communities around them. In so doing, he fostered the careers of many young social and behavioral scientists interested in promoting adolescent health by addressing teen alcohol use – one of the primary causes of preventable morbidity and mortality globally. Well-known for his leadership of the Harvard College Alcohol Study, his trainees and students knew him as a family man – proud of his children and devoted to his wife. “Aging,” he would tell me before heading out to play tennis, “was not for the faint hearted.” A few years ago, I hiked in the Pyrenees mountains that border France and Spain, and then walked a portion of the Camino de Santiago, the famed pilgrimage route along Spain’s Atlantic Coast. Amid crushing refugee crises and rising xenophobia in the United States, I wanted to honor refugees who were walking all over the world to find safety. I chose my route with Henry in mind. As a Jewish child fleeing Poland during World War II, he and his family had traveled from Poland through Europe. Like many European refugees at that time, they found themselves walking through the Pyrenees toward Portugal and safety – ultimately settling in the United States. The Pyrenees are awe inspiring, beautiful, massive, sheer. It is hard to imagine Henry as a little child hiking through them. As a mother, you sense the absolute urgency of the flight to safety of refugees who choose such routes. I wonder whether Henry’s early life experiences of uprootedness set him on the path toward researching the circumstances governing health choices and behaviors of youth. In talking about college drinking, he would recite with great specificity the number of youths who died each year from alcohol-related causes, asserting that even one was too many. He would not give up on them, he repeatedly told me. And he didn’t. Some 80 papers resulted from this work, international programs replicated his studies, his students went on to successful careers, and the public’s understanding of the negative effects of alcohol use in college changed. Programs developed. Policies improved. As a scholar, Henry built a thriving research program while staying connected and kind. He leaves a legacy of people, papers, impact, and the model of a life well lived.

Nancy Krieger, Professor of Social Epidemiology

I vividly remember Henry’s guidance the first time, as junior faculty, I was reviewing student applications for admission into our department. He urged looking for the students who had a clear grasp of what public health is and how they hoped to contribute – and emphasized looking at the student statement first, and only then review their trajectory of performance from undergrad to wherever they were at the point they applied. It was sound advice from someone who had not only reviewed a zillion applications over the course of his career, but also had a keen sense of which students developed & thrived in the program. When someone with more experience can share wisdom gained with a junior colleague as he did, it is definitely a gift!

Loretta Alamo, Assistant Director of Operations and Administration, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences

I am deeply saddened to hear of Dr. Wechsler’s passing. I enjoyed my time working with him in Behavioral Sciences – the Department’s long-ago name. He was a gentle soul and wonderful to work with. His dedication to his research on College binge drinking has had a profound impact on the world today. I remember all those “paper” surveys and mailings that went to so many students at many colleges. His course instruction around alcohol issues was always interesting and powerful to all. May he rest in peace.