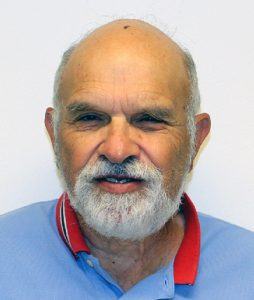

Noel Weiss, Professor Emeritus in the Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, is an epidemiologist who has worked extensively on the causes of cancer. He also has been engaged in the development of epidemiologic methods and on the application of these methods to the understanding of the determinants of the outcome of illness. Weiss is widely recognized not only for his impressive research contributions, but also for his outstanding teaching and mentorship. As a graduate from our department fifty years ago, we took this opportunity to ask Weiss to reflect on his experiences during that time, as well as on the development of his career and on the field of epidemiology since then.

Noel Weiss, Professor Emeritus in the Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, is an epidemiologist who has worked extensively on the causes of cancer. He also has been engaged in the development of epidemiologic methods and on the application of these methods to the understanding of the determinants of the outcome of illness. Weiss is widely recognized not only for his impressive research contributions, but also for his outstanding teaching and mentorship. As a graduate from our department fifty years ago, we took this opportunity to ask Weiss to reflect on his experiences during that time, as well as on the development of his career and on the field of epidemiology since then.

Take us back to April 1971… What are your recollections from your time in our department? What was the environment like? What could a visitor expect to find when entering the department?

We were located in the building on 655 Huntington Ave. (The building on 677 Huntington had yet to be built). Epidemiology was on the 2nd highest floor (13?) – Biostatistics was directly above. There were classrooms of modest size in the building, but no actual lecture halls – for School-wide lectures we would go to 1 Shattuck Street. Each doctoral student had his/her own tiny office, and that space was much appreciated. The larger offices on the floor were used by faculty – MacMahon, Abelin, Segal, Miettinnen, Cole, Monson, and Mack – and by the staff carrying out the faculty members’ research.

There were no personal computers back then, and the only electronic calculators were giant devices that had to be shared. There was an enormous computer on the floor below us (which I never used), along with punch cards, a card sorter, and a card reader. As I recall, we would put the cards in the reader and have the contents sent to a Harvard computer in Cambridge, the output sent back to us on paper the next day. I remember doing (and enjoying) my programming in SPSS.

In terms of the topic for your thesis “Arteriosclerosis Obliterans: A Case-Control Study,” how did you pick it? What was your process in choosing a topic?

I was interested in doing work on cardiovascular disease in women, no doubt resulting from my mother’s heart problems in her 40s (she lived in relatively good health for another 50 years). I had the idea of using the data from the Framingham Study to study a possible connection between a history of oophorectomy and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. I had mentioned this to Bob McGandy in the Department of Nutrition, and he and I went to Framingham to meet with William Kannel, who was running the operation there. Though Kannel thought it was a fine idea, the project was nixed by higher ups at the (then) National Heart Institute; they were funding the study, and wished to take this question on themselves.

I was VERY disappointed, but regrouped and developed a plan to address the causes of a related condition (peripheral artery disease) in women using a case-control study. My advisor, Brian MacMahon, okayed this (with a modification to include men), and committed the Department to provide some modest data collection costs. A happy ending!

What was the thesis writing process like for you? Were there any particular challenges? Any unexpected surprises?

My dissertation consisted of four articles, each of which went on to be published. The only thing I remember about the writing was the help that Brian MacMahon provided. His reviews of my drafts were prompt and constructive. I had already read a number of his articles, and I’m sure that (unintentionally) I sought to mimic his style. But getting his direct input on my own work was a major factor in developing my skill in communicating my thoughts.

I very much appreciated Brian’s accessibility, as I did that of Jane Worcester in Biostatistics, with whom I had numerous conversation both prior to and during the dissertation process.

How would you link the work you did in your thesis to what you would go on to do in your later years as an epidemiologist?

My first two years after leaving Harvard were spent with the National Center for Health Statistics, and during that time I continued to do work in cardiovascular disease. Then in 1973 I joined the faculty in Epidemiology at the University of Washington, initially with the expectation that I would keep on this research path. But as has been noted by others, man plans and God laughs. The funding for my position shifted, and I was asked to develop and lead a population-based cancer registry in Western Washington. And just like that, for the next 40 or so years I was a cancer epidemiologist.

My time at Harvard was crucial in guiding the direction of my professional life. I arrived having a vague interest in public health, and left knowing that epidemiology was exactly what I wanted to do. And more specifically, I knew that I wanted to ply my trade within a school of public health. As of this writing, I’m 78 years old, still working and enjoying part-time teaching and advising. A testimony to a good career choice!

(Curiously, after a hiatus of more than 40 years I had an opportunity to make one additional contribution in the area of peripheral artery disease: I used data from the MESA study to examine the ability of a low ankle/brachial index (suggestive of impaired blood flow to the legs) to predict the development of symptomatic arterial insufficiency. Nice to be able to come full circle).

Curious to hear your thoughts on the development of epidemiology from that time onwards, what would you say are some recent developments that you are most excited about?

In my opinion, the most important change has been in the availability of data. In many parts of the world the computerization of medical records has enabled the relatively inexpensive and relatively complete enumeration of a wide range of health outcomes. This has led to an improved ability to document the incidence of illness, and also has made more feasible the conduct of cohort and case-control studies of disease etiology. Those same records allow for the ascertainment of treatments prescribed by health care providers and administered in health care settings, which have been crucial for the growth of the subarea of clinical epidemiology.

What advice would you give to current students in the department? Is there something you wished you’d known during your time as a student?

Considering a career as an epidemiologist? The practice of epidemiology involves, of course, the search for the causes of human disease and injury. It is true that, if you go into this field, you will (like all of us) experience days of frustration, and days during which there is no discernible progress towards understanding those causes. Nonetheless, you will never have to question the importance of what you are seeking to accomplish. Also, the work generally is intellectually stimulating, and with increasing experience you’ll get better and better at it. Finally, along the way you’ll get to meet and interact with a lot of nice people. What’s not to like?

–Coppelia Liebenthal