In a recent Twitter thread, Harvard Biostatistics and Statistics professor Xihong Lin announced the publication of a study in JAMA carried out in collaboration with colleagues at Tongji School of Public Health of Huazhong Science and Technology University analyzing the public health interventions that took place during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. The study was based on an analysis of 32,000+ lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases in Wuhan, and was updated from the MedRxiv pre-print of an analysis of 26,000 cases by adding 6,000 cases and a fifth period of analysis lasting up to March 8. In the absence of a vaccine or effective treatment, public health interventions are particularly important to control the epidemic.

In a recent Twitter thread, Harvard Biostatistics and Statistics professor Xihong Lin announced the publication of a study in JAMA carried out in collaboration with colleagues at Tongji School of Public Health of Huazhong Science and Technology University analyzing the public health interventions that took place during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. The study was based on an analysis of 32,000+ lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases in Wuhan, and was updated from the MedRxiv pre-print of an analysis of 26,000 cases by adding 6,000 cases and a fifth period of analysis lasting up to March 8. In the absence of a vaccine or effective treatment, public health interventions are particularly important to control the epidemic.

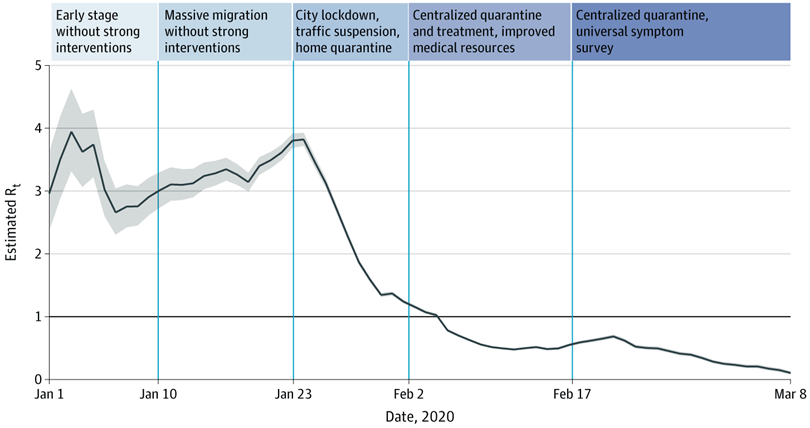

The study found that key interventions, including lockdown, a traffic ban, home quarantine, centralized isolation of the infected, suspected subjects and close contacts of infected subjects, and a universal symptom survey in conjunction with early treatment substantially slowed the spread of the virus.

It took Wuhan 6.5 weeks to reduce R, the average number of infected subject by a case, from >3 to 0.1. This involved 1.5 weeks of social distancing and five weeks of centralized isolation and quarantine measures in addition to social distancing, over a period lasting from January 23 to March 8. The city was reopened on April 8 after two weeks of no confirmed cases.

The results of the intervention effect of social distancing were replicated in multiple countries, such as Italy and Germany, where R values have lingered around 1 for a month. These results indicate that social distancing is not good enough to bend the curve, mainly due to continued household transmission that occurs under home quarantine. By contrast in Wuhan, centralized isolation of infected and quarantine of symptomatic subjects and close contacts of infected helped bend the curve, resulting in the drop of the R value as low as 0.1.

Field hospitals in Wuhan admitted test-positive patients with mild/moderate symptoms, so these patients could receive early treatment and be closely monitored by medical staff to prevent their illness from becoming severe. This helped block the transmission chain and protect family members. It also helped reduce the number of deaths, and the burden on ICUs, ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), and health care workers.

The analysis of the Wuhan data showed that elderly people were at a higher risk of infection and were more likely to be severe/critical cases (RR=2.3 for 60-79 and RR=3.6 for 80+). Children had a much lower risk of infection than adults, but the risk continued to increase over time when the rates in adults dropped. Health care workers also had a much higher risk of infection than the general public when not protected by PPE.

To fully control for the epidemic in the U.S., multi-faceted measures are needed which include six pillars: mask wearing, social distancing, wide testing, contact tracing, isolation of infected patients and quarantine of symptomatic subjects and close contacts, and treatment of infected patients. Because each country is different, effective implementation of these control measures must be adapted to each country’s situation and culture.

Under represented minorities in the U.S. have been found to have a much higher risk of infection and death, resulting in rising concerns over health disparities in the COVID-19 era. Such health disparities are currently underscoring the need to develop effective isolation and quarantine measures to segregate infected subjects and begin early treatment. Household transmission is of particular concern for low-income families and under-representative minorities because of poor housing conditions and the continued need to leave the home to work.

Increasing testing capacity, one key area in which the U.S. is lagging, is also necessary to block the transmission route, and help with early diagnosis and treatment. In the shortage of testing capacity, priority should be given to high risk and vulnerable groups including healthcare workers, the elderly, nursing home residents and workers, family members and close contacts of infected, essential workers, low income families, and underserved populations.

Finally, effective public education and communication is critically important, both to share newly gained scientific knowledge and to inform the general public to make good decisions for loved ones and communities. Combatting the virus demands a multi-stakeholder approach that engages our government, international organizations, academia, business, community and citizens to care for our loved ones, minimize economic damage, and quickly return to work and some state of “normalcy”.